It’s easy to put a finger on the problem that is the Long Beach digital divide. The issue: U.S. Census Bureau statistics show 25 percent of residents do not have broadband service — and 10 percent go online at home only because they possess a smartphone.

Related: Helpful information for Long Beach residents trying to connect to the web

Looking for an easy solution? Sorry, there’s no APP for that. Yet.

According to experts, there is no single, cure-all strategy that will bridge the great economic and electronic divide of the 21st Century in ethnically diverse Long Beach. Rather, solving the problem will take a combination of strategies and key players.

It will require that state officials, city officials, school administrators, the telecommunications industry, community organizations, broadband advocates, entrepreneurs and others all work together to apply the most promising ideas, they say.

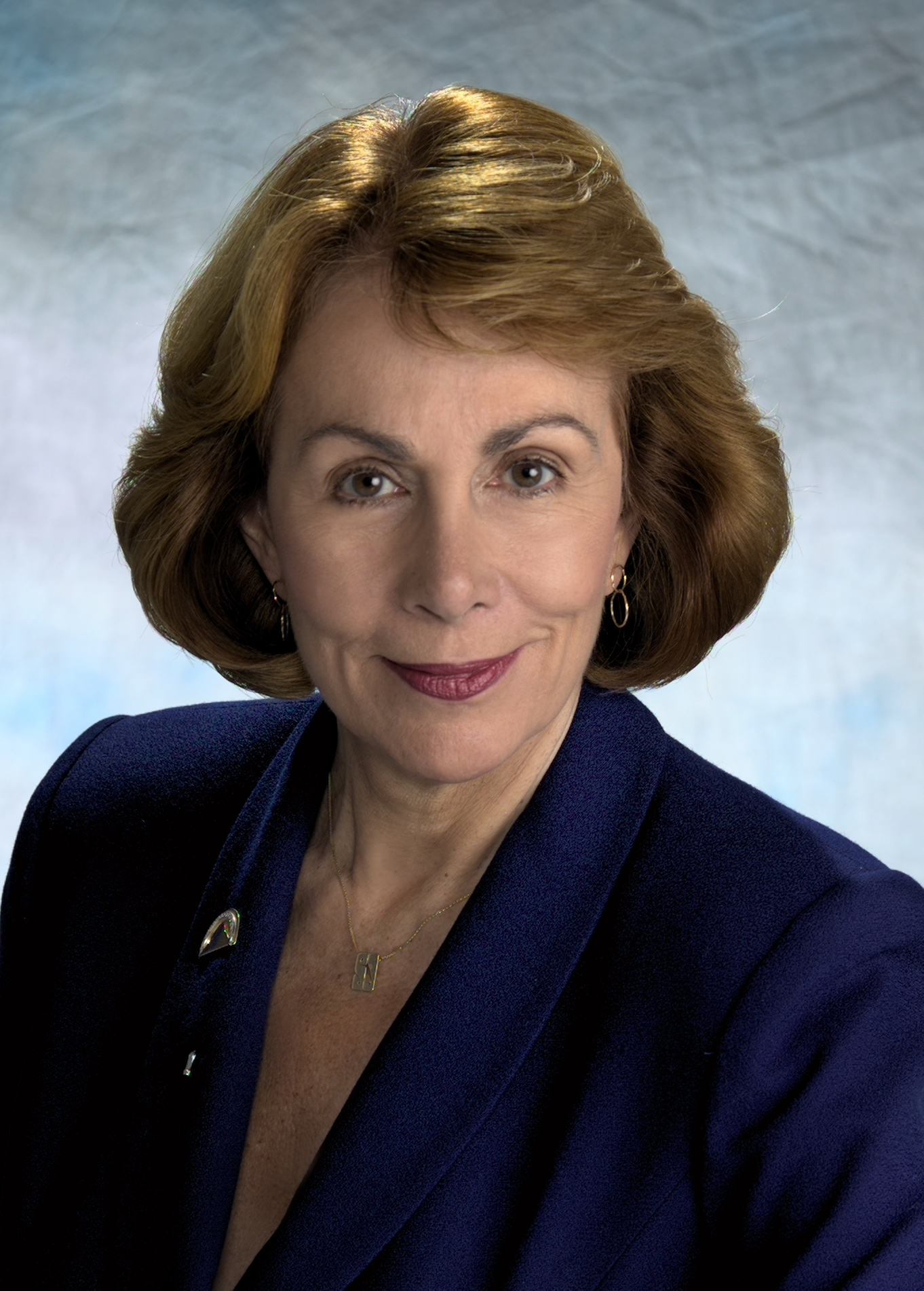

Gwen Shaffer, Cal State Long Beach. (Courtesy photo)

“None of these stakeholders, unilaterally, is capable of making universal broadband a reality,” said Gwen Shaffer, a journalism professor at Cal State Long Beach who specializes in internet access issues.

“And it goes without saying that closing the divide transcends the simple provisioning of internet access,” Shaffer said. “Broadband connections must be affordable for even low-income households, and they need to be accompanied by ownership of reliable PCs.”

As well, she said, none of that will do any good unless people are taught how to take full advantage of devices that are, for many, complicated, expensive and intimidating.

Got to be savvy

The divide can be stark. And it is concerning that those most likely not to have internet are poor, minorities and people with limited education

But it is encouraging that many in Long Beach recognize the problem and are doing something about it.

Take Centro CHA, for example.

This community group, which serves the city’s huge Latino community, teaches classes on using computers and navigating the internet and provides training for people trying to find employment in the digital age.

On one recent day, all but one of the group’s 14 public computers was being used in the bustling office. Young men were polishing resumes, searching for jobs, applying for openings and working on certifications for food handling and retail positions, said Jessica Quintana, executive director.

Case manager Alfred Escobar helps Giovanni Franco refine his resume during Wagee workshop at Centro CHA (community Hispanic Association) in Long Beach. Centro aids latino youths seeking employment get counseling on producing resumes and use of computers for applying to jobs online. (Photo By Robert Casillas, Daily Breeze/ SCNG)

“Everything is online,” Quintana said. “You don’t just walk into a place and say, ‘Can I have an application?'”

And there is more to applying than typing a few words and hitting the send button.

“You’ve got to be able to be savvy to navigate the technology system of the employers,” she said.

Centro CHA is happy to provide the training, but Quintana said covering program costs is difficult.

“We’re struggling all the time to meet the needs of the city’s constituents,” she said. “That shouldn’t be something that we do all by ourselves.”

Fast enough for homework

That’s where the state may be able to help.

Sacramento has labored for a decade, with limited success, to bring broadband to remote regions. The state uses cash from a fee on telephone bills to subsidize construction of telecommunication infrastructure in rural areas.

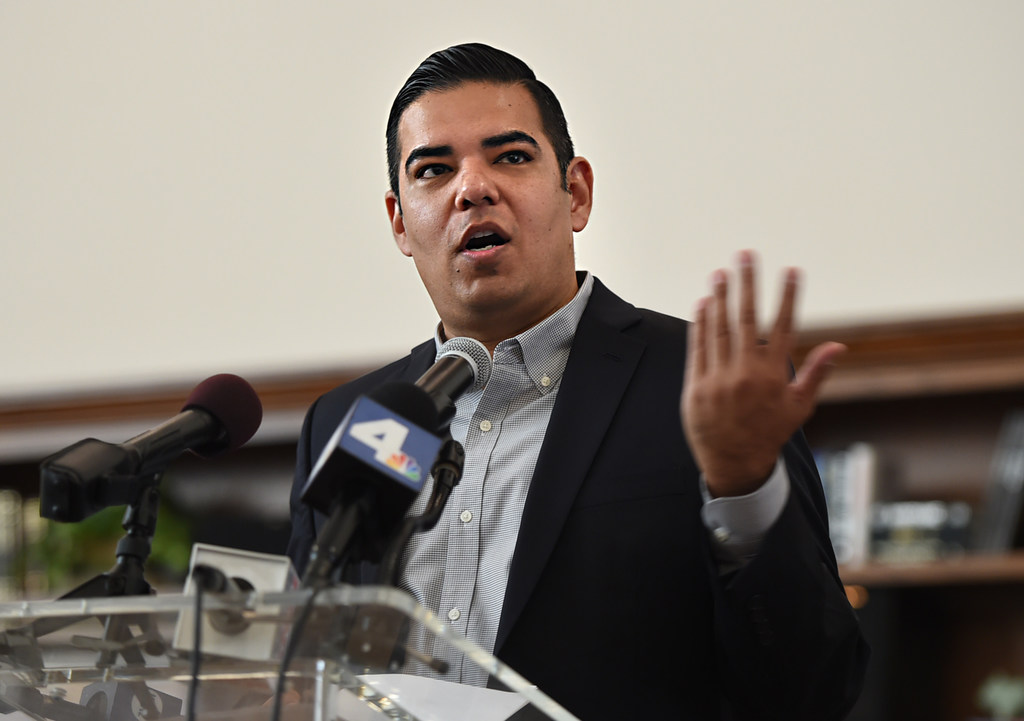

Assemblyman Eduardo Garcia, D-Coachella (Courtesy photo)

A new law authored by Assemblyman Eduardo Garcia, D-Coachella, has extended the program.

The legislation also introduced an urban element that could help groups in Long Beach that aid those on the wrong side of the digital divide. It created a $20 million “broadband adoption account” intended to defray groups’ costs.

In Long Beach, the problem is not so much broadband isn’t available in a particular neighborhood, but that many residents cannot afford to subscribe to a service.

Students fill the computer lab to work on their projects at the YMCA of Greater Long Beach’s Youth Institute, which helps students learn computer skills. (Photo by Scott Varley, Press-Telegram/SCNG)

That underscores the importance of the work groups such as Centro CHA and the YMCA of Greater Long Beach do, providing banks of computers for people to use, training people to navigate the internet and helping them sign up for low-cost home broadband service. Those kinds of services must continue to be provided, and on a larger scale.

And signups for low-cost broadband are going to be crucial, experts say.

But such programs are available, thanks in part to the California Emerging Technology Fund, a nonprofit corporation working to close the divide across the state through legislation such as Garcia’s — and negotiations with major internet players.

Sunne Wright McPeak

Sunne Wright McPeak, chief executive officer and president, said the group negotiated agreements with internet providers during the past couple of years to create low-cost broadband programs. And now, she said, all the major providers have such a choice for consumers.

“These are really good offers for students to do their homework, to take an online course,” McPeak said, although, “You might find it slow if you do a whole lot of movie downloading.”

Offer for poor families

Providers serving Long Beach are among those who have extended offers to low-income families.

Dennis Johnson, a West Coast spokesman for Spectrum, said, for example, that qualifying families and senior citizens in Long Beach can sign up for a service called “Spectrum Internet Assist.”

Spectrum’s offer features high-speed internet for $14.99 per month with no modem fees, data caps or contracts, Johnson said in an email.

Frontier, meanwhile, launched an “Affordable Broadband” program in August 2016.

For $21.99 per month, subscribers get high-speed internet, a free Chromebook laptop and a free wireless router, with no monthly contracts, said Javier Mendoza, a spokesman for Frontier Communications in Long Beach.

To qualify, Mendoza said, a household must participate in the California LifeLine Program, which provides discounted land-line and cell-phone service.

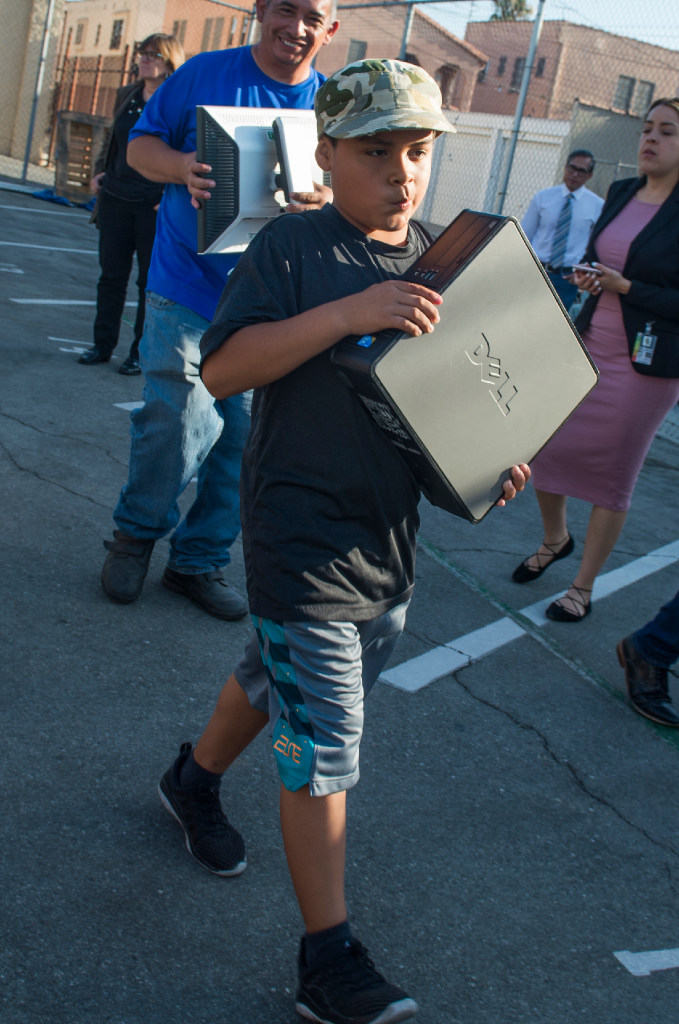

Kevin Vasquez, 9 of Los Angeles, walks away with a computer following an event in South Los Angeles on Thursday, August 3, 2017. The event was organized by Long Beach-based human-I-T, which refurbishes old computers and gives them to low-income families through a city of L.A. program. The partnership is an example of what could be done in Long Beach to help bridge the digital divide. (Photo by Thomas R. Cordova, Press-Telegram/SCNG)

Mendoza said households get into the Lifeline program if their income is within certain limits, he said, or if they are enrolled in one of several public-assistance programs. Those include: Medi-Cal, Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Federal Public Housing Assistance or Section 8, CalFresh, Food Stamps or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Women, Infants and Children Program (WIC), National School Lunch Program (NSL) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

“We recognize that for some — particularly persons and families living in underserved communities or below the poverty line — the cost of internet access excludes them from necessary and vital services; services… many of us often take for granted in the digital age,” Mendoza said.

According to a news release announcing the launch, Frontier is aiming to sign up 200,000 low-income households statewide over two years.

How successful the program has been is unclear. Mendoza would not say how many Long Beach families Frontier has enrolled to date, saying, “subscriber counts are proprietary information.”

Two-for-one solution

Frontier’s decision to throw in a free device targets another challenge families face: many cannot afford a computer, either.

That’s something Gabe Middleton and his friend, James Jack, were well aware of when they founded in 2012 a nonprofit called human-I-T, which has an administrative office in downtown Long Beach.

“We knew that there was a ton of people who don’t have access to good working technology, nor the internet, nor the skills, and they’re being left behind,” Middleton said.

They also knew electronic waste was a mounting problem.

Long Beach City Councilman Rex Richardson (File photo)

Now, human-I-T partners with the city of Los Angeles and Frontier Communications to reduce the amount of electronic waste and place computers in low-income households. Through an innovative recycling program, they take donated laptops and personal computers people throw out, refurbish the devices and make them available for free.

While that program is focused on Los Angeles, Middleton said in an interview he was open to the idea of replicating the fix-and-give-away model in other major cities. Perhaps such an initiative could be used to put more computers in the hands of low-income Long Beach residents.

Long Beach Councilman Rex Richardson said city officials have initiated discussions with human-I-T about the possibility of targeting middle school students in neighborhoods where families cannot afford computers.

Library learning

McPeak said it is crucial that as many as possible have the ability to go online at home.

However, many still do not. And while the community strives toward that goal, it is helpful to have 266 public-use computers at the city’s dozen public libraries.

Kate Azar, executive director for the Long Beach Public Library Foundation. (File photo)

Kate Azar, executive director for the Long Beach Public Library Foundation, said those libraries also have Family Learning Centers where kids get help with homework and adults get assistance applying for jobs.

Azar said the foundation provides $1.2 million a year for the library system. Much goes for the Family Learning Center program.

It is clear that Long Beach’s libraries play a key role. Grandparents, school children and college students are a constant presence on the public computers.

“If you walk into any one of our 12 libraries, it’s quite obvious that people do not have the access to 21st Century digital resources at home,” Azar said last week.

Vanitha Chandrasekhar, education technology coordinator for Long Beach Unified School District, said earlier that educators realize that. So teachers make time in class for kids to complete internet-based assignments.

She said some schools keep their libraries open after the final bell rings, too, so kids can finish such assignments.

And the district coordinates with city libraries.

Closed too early

Those libraries have stood in the digital gap and have been a shining example of what needs to continue.

But are they doing enough? Some think not.

One is Eric Baiye, an electrical engineering student at Long Beach City College looking to transfer to Cal State Long Beach in fall 2018.

Families and students take advantage of the available internet connected computers at the Michelle Obama Library in North Long Beach on Thursday, November 9, 2017. (Photo by Scott Varley, Press-Telegram/SCNG)

Baiye said he can’t afford broadband. So he spends most of his time at the college, using its free Wi-Fi. He supplements that access with two to three visits a week to the Michelle Obama Neighborhood Library.

Baiye said the library is convenient because it is close to his North Long Beach home. He also said he’d visit more often if it had better hours.

“They close too early and they open too late,” he said.

Azar acknowledged expanded hours are needed, but finding funding for that is going to be difficult.

Public living room

Long Beach City Councilmember Lena Gonzalez (File photo)

Of course, residents without home access can always run down to the local coffee shop. Or, to any number of city-operated facilities.

Long Beach provides free Wi-Fi at parks, pools and the senior center, officials said. There is even a “Wi-Fi corridor” along Atlantic Avenue, connecting the Michelle Obama library, Houghton Park and Jordan High School.

That new corridor, said Councilman Richardson, who represents North Long Beach’s Ninth District, is just shy of a mile long.

“We’re creating a public living room where people can go,” Richardson said.

He said the WiFi corridor is a model that could do much to connect families without home internet and should be replicated throughout the city.

First District Councilwoman Lena Gonzalez has talked of doing something similar in her westside district, in an initiative she is calling “Project 90813.”

The private sector has played a role, too, in providing such hot spots, and could play a larger one.

For example, Mendoza said Frontier created a Wi-Fi connection to serve the community group Khmer Girls in Action.

Fiber master plan

In part, success in bridging the divide may depend on how the Long Beach City Council implements a new fiber master plan.

Bryan M. Sastokas, Long Beach technology and innovation chief. (File photo)

“We don’t have a plan that is specifically targeting the digital divide,” said Bryan Sastokas, the city’s technology and innovation chief. “But we understand there is a need.”

Sastokas said the city is considering expanding its existing 62-mile fiber network to 110 miles. The goal is to connect isolated city-owned buildings and facilities to the system.

Once the new fiber is in place, he said, opportunities to partner with the private sector may arise to strengthen the signal in places where it is weak now.

“That should put us in a position to serve some of the unmet need,” he said.

This week, Long Beach officials are poised to consider a $67 million initiative to replace outdated communications equipment, invest in technology systems to advance cyber security and other goals, and to nearly double the size of the fiber network, according to Sastokas. The fiber expansion piece is projected to cost $11.9 million.

The City Council is scheduled to consider the matter Tuesday.

A little bit of everything

Long Beach may be able to learn from the example of Santa Monica, in terms of what to do with additional fiber.

In 2006, Santa Monica started leasing unused sections of its fiber network to businesses. Later, the city connected residential areas.

Two years ago, Santa Monica piped internet into 10 affordable-housing-project buildings. Each building has a community room where residents can go and feast on fast and free internet, Santa Monica officials said. Now, the city is gearing up to connect 30 more such buildings.

Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia (File photo)

While fiber expansion is a promising tool, experts say, all the available tools in the toolbox are needed. Computer giveaways, public-use computers, digital literacy training, state grants, federal grants, public Wi-Fi, business-provided Wi-Fi, school innovations and more will have to be utilized to their full potential if the dream of bridging the divide across Long Beach is going to be realized.

Mayor Robert Garcia summed it up this way: “We have to do a little bit of everything.”

Long Beach Media Collaborative participants Karen Robes Meeks of the Long Beach Business Journal, Ashleigh Ruhl of the Grunion Gazette and Jason Ruiz of the Long Beach Post contributed to this report.

Comments are closed.