Technology has rapidly changed virtually everything in the classroom.

Modern-day geometry students equipped with three-dimensional printers can transform their math lessons into physical shapes. Interactive software lets biology learners build accurate models of plant and animal cells. Electronic textbooks offer word definitions with a simple touch of the screen.

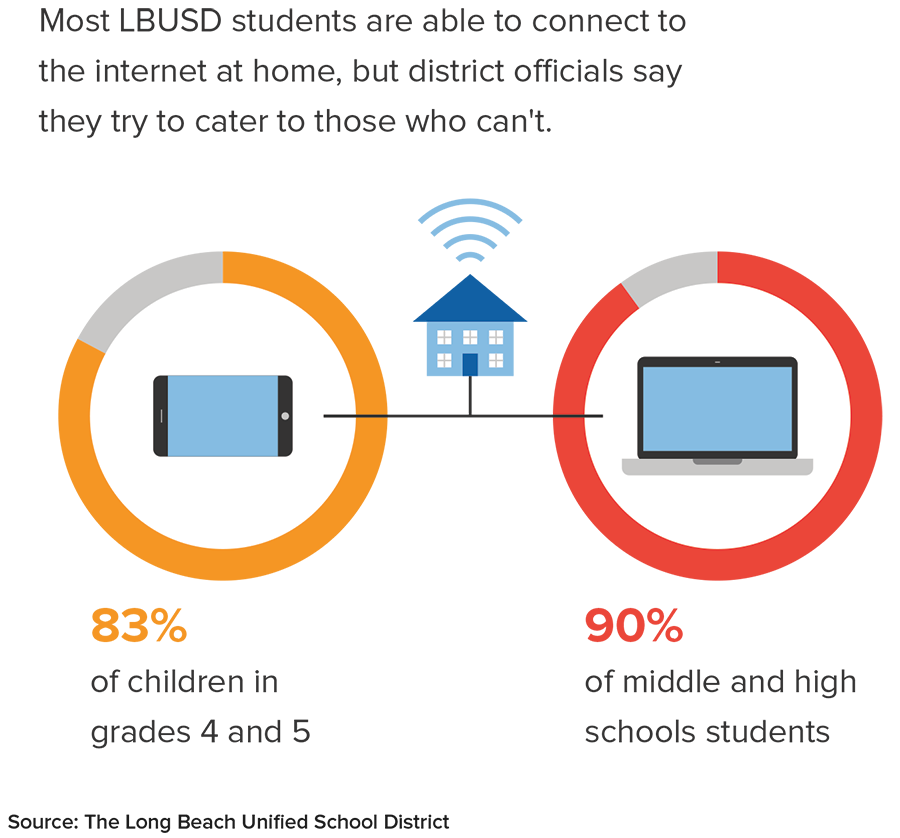

The dramatic evolution is exciting, but also onerous, for teachers — who are expected to adhere to ever-changing academic standards, while navigating increasingly more complicated devices and computer programs. The achievement gaps are still there, of course, but now so are technology gaps: 17% of Long Beach Unified School District fourth- and fifth-graders, and 10% of high schoolers, do not have access to computers or the internet at home, according to district figures.

That’s part of the reason computer literacy, particularly internet literacy, is folded into LBUSD’s curriculum at almost every level.

“Ten years ago, you couldn’t imagine we would be where we are now,” said Chris Eftychiou, spokesman for the school district. “It’s evolved so rapidly.”

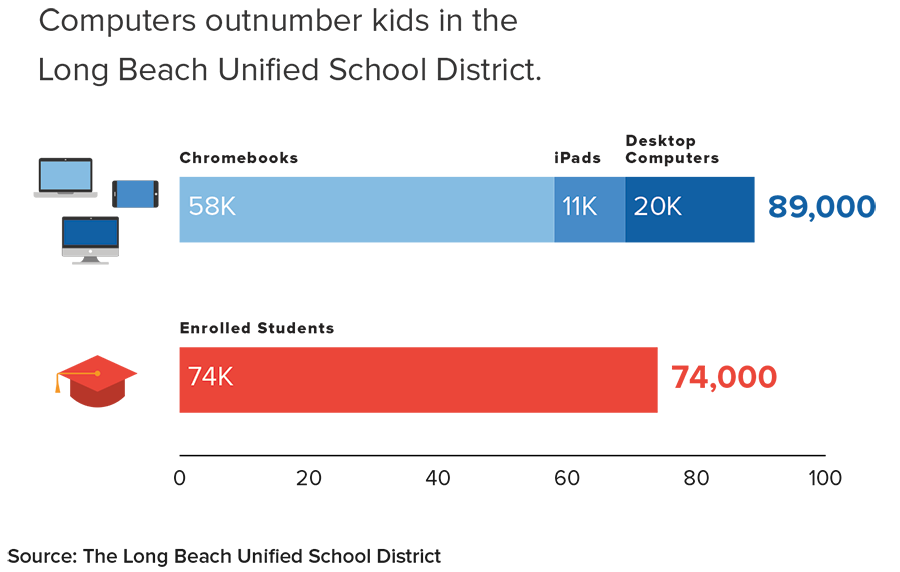

And the district is well ahead of the game, according to LBUSD Superintendent Christopher Steinhauser. Computers now outnumber kids, with Long Beach Unified’s 74,000 enrolled students having access to about 58,000 Chromebooks, about 11,000 iPads and more than 20,000 desktop computers.

“The Chromebook and iPad are becoming like the pen and pencil,” Steinhauser said.

Teachers fight to close the gap

The U.S. Census Bureau found that 14% of Long Beach residents younger than 18 live in households without internet access. Another 9.5% of households only have access through smartphones. The vast majority of the disconnected are people of color and the poor. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 25.7% of high school dropouts have no internet access at home.

Vanitha Chandrasekhar, educational technology coordinator for LBUSD, acknowledges that she and other educators are warriors of sorts — fighting on the frontlines of the digital divide, trying to provide every student in Long Beach with equal opportunities, despite whatever challenges those youngsters may face at home.

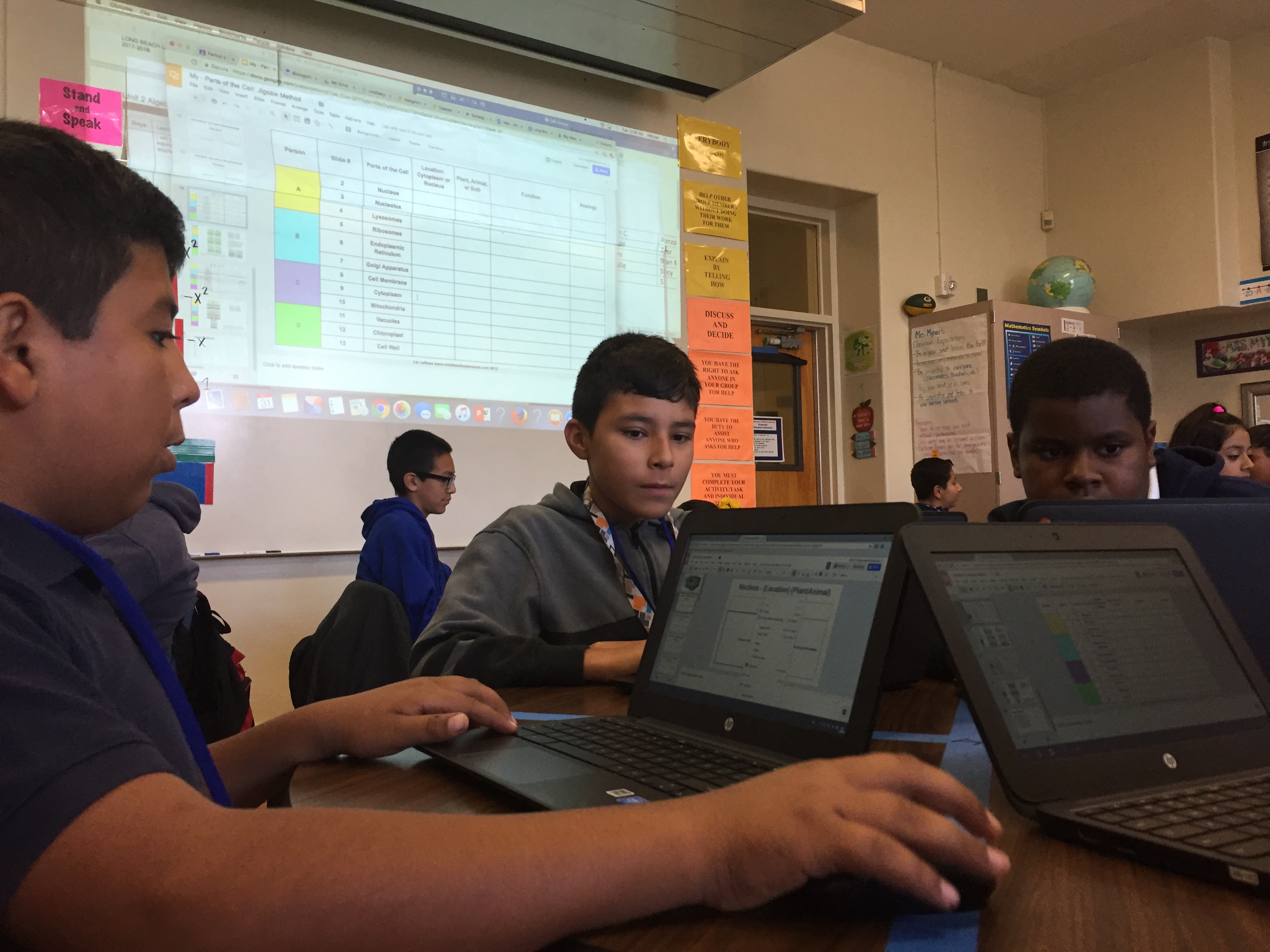

Lindbergh Middle School students, from left, Tyler Bernal, Alonzo Castanon and

Bryan Magdaleno do their classroom work on Chromebooks. During their sixth grade science class, they collaboratively use the computers to study digital plant and animal cells. Gazette photo by Ashleigh Ruhl

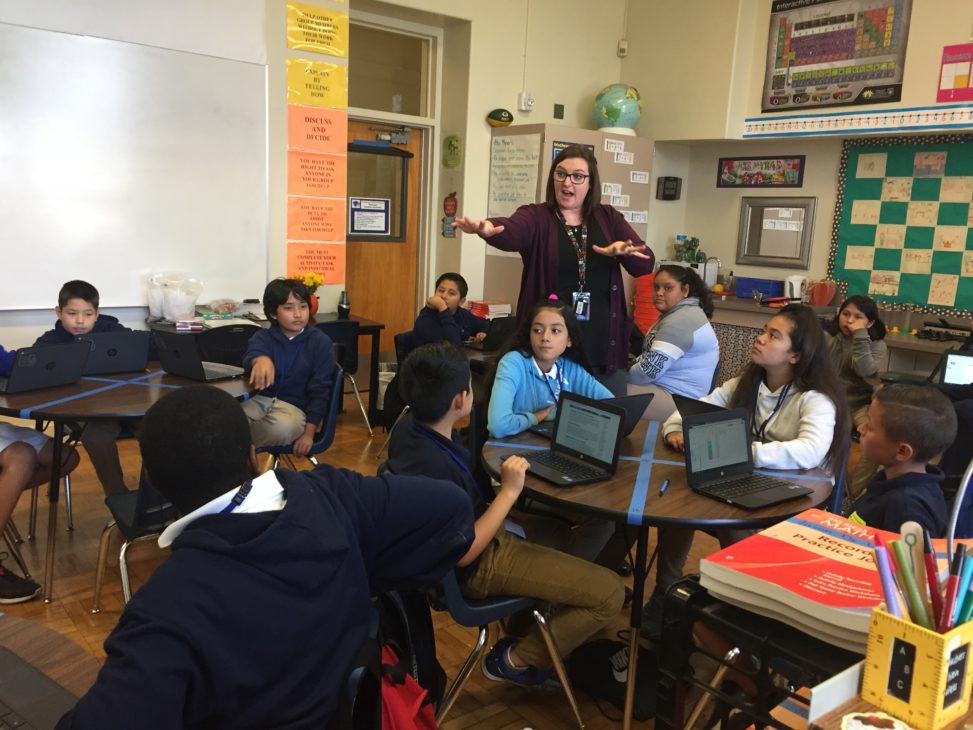

Amy Becker, an LBUSD technology teacher on special assignment at Lindbergh STEM Academy, is one such warrior. Becker can tell almost immediately if her students, especially those entering from elementary school, have had limited access to the internet outside of the classroom.

“Those without access at home enter the sixth grade at a huge disparity,” she said, adding that children without residential access may have less opportunity to explore and be creative with the technology or utilize educational programs.

Becker said teachers at Lindbergh work hard to help the less tech-savvy get up to speed, and she is convinced the students do catch up, but teaching the kids how to use technology is only part of the battle.

“The teachers know that not every kid has access at home, and they make great efforts to work around that,” said Lindbergh Principal Dawn Lomeli. “The bulk of the work has to be done in the classroom… If anything is electronic, we know we have to provide enough time for it to be done in class.”

Using the school’s library or computer labs isn’t really an option. The technology in the computer labs is being phased out in favor of purchasing the more versatile Chromebooks, and the school’s library is closed every other week because Lindbergh’s librarian splits her time with Keller Middle School.

Lomeli said much is up to the 25 teachers on staff, a resourceful bunch who have embraced technology, to provide kids with the experience they need. Many of the jobs these students will someday hold have not even been invented yet.

“I have teachers doing more than they’ve ever been asked to do,” Lomeli said.

Devices build a bridge

The influx of mobile devices at LBUSD has been swift, Steinhouser said, with Chromebooks only having been introduced in the district in 2015 and iPads being piloted at middle schools starting back in 2012.

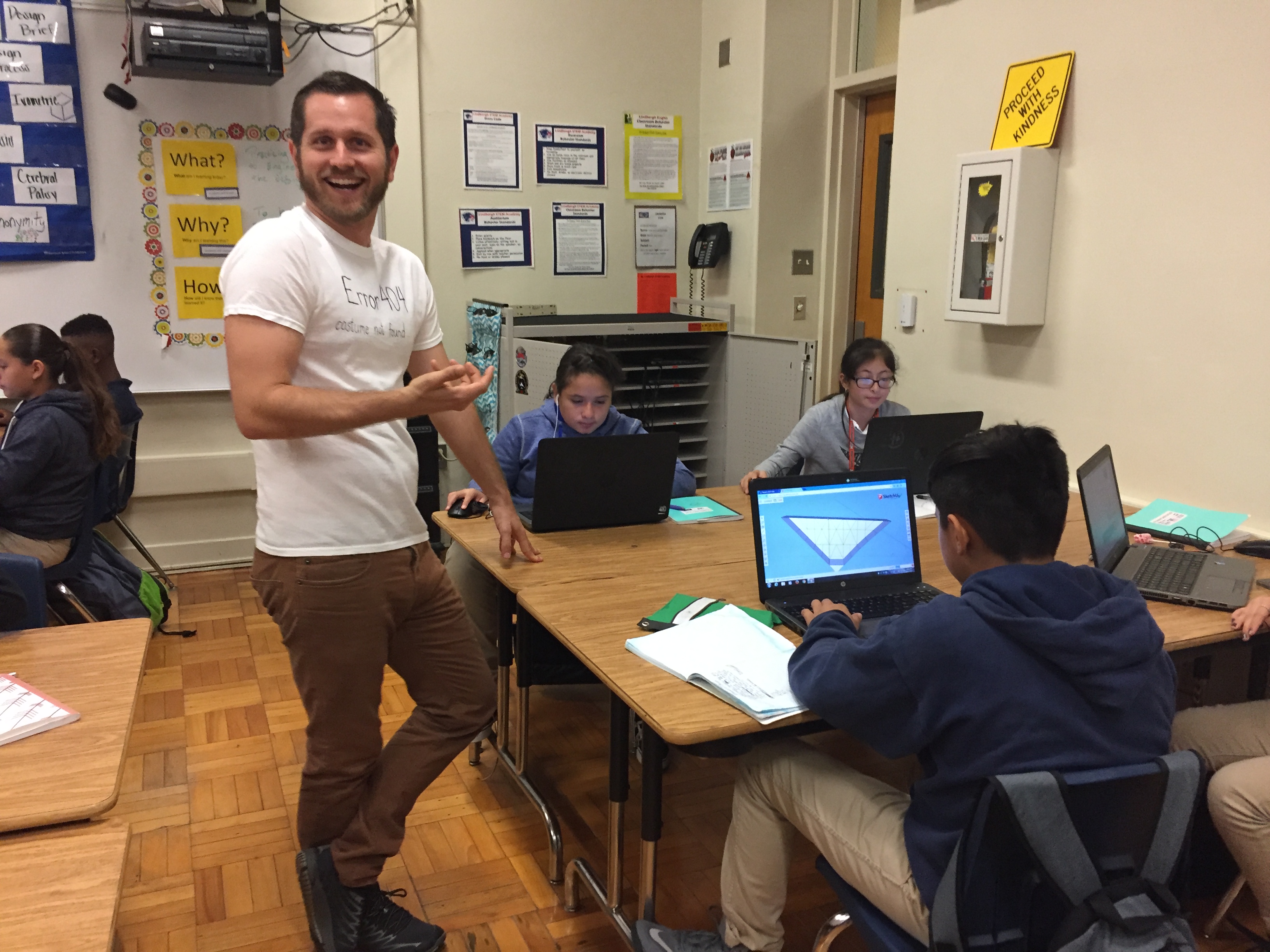

Teacher Christopher Thyden, in his third year at Lindbergh Middle School, instructs students in a class called Project Lead The Way. It’s an advanced STEM-focused course that challenges students to solve challenges using advanced software, including three-dimensional printers. Gazette photo by Ashleigh Ruhl

A few schools have both a Chromebook and an iPad for every student, putting devices per pupil at a 2-to-1 ratio. About 40 of the district’s 84 schools have a 1-to-1 ratio of Chromebook or iPads per student, and all schools have at least a 1-to-2 ratio, he said.

“We are in great shape,” the superintendent said, noting that the priority has been on modernizing high and middle schools first, with elementary levels not far behind. In fact, there are more devices on the way this year, with purchase orders totaling $6 million, the highest budgeted spending on such devices in the district’s history.

“All the sites are moving toward a 1-to-1 ratio,” he said. “This year, we wanted all elementary schools to be 1-to-1 in grades 3 through 5, and they’ll all be by the end of this (school) year.”

The ultimate ideal, according to Eftychiou, would be for every student to have his or her own device to take home. But he emphasized the district already has come a long way in a short amount of time.

That’s certainly true at Lindbergh, named after the famous aviator, which is one of the best-equipped in the district in terms of technology. The ratio of students to devices is 1-2, with every student having access to both an iPad and Chromebook.

The airplane-shaped school in north Long Beach is one of the district’s oldest and smallest, and also among the poorest — 94% of the total 645 students qualify for free or reduced cost lunches because their parents’ incomes are below the poverty level. By comparison, Long Beach Unified’s overall rate is 69%.

Part of the reason Lindberg is so well stocked is because it was officially designated as a STEM Academy in 2014, emphasizing science, technology, engineering and math curriculum, and requiring the integration of more tech into every class, Lomeli said.

But that doesn’t help with access at home.

When the school tried sending home iPads for each student, teachers soon realized that wasn’t going to do much good.

“There were issues with loss and damage, and many of the kids didn’t have (internet) access at home…” Lomeli said. “It just didn’t make sense to send them home anymore.”

Becker added: “Students and parents were relieved when we stopped sending the iPads home because they didn’t want that responsibility.”

Parents a big factor

The biggest challenge in bridging the divide, at least at Lindbergh, Becker said, is working to connect with internet-free parents, many of whom are struggling just to put food on the table.

Those are the parents who often aren’t online, where LBUSD offers programs such as Parent Vue and School Loop. Each program has different functions, but essentially both are designed to help parents stay connected — with options such as daily emailed progress reports, digital transcripts, email access to teachers, school-of-choice applications and more.

Only about half of Lindbergh parents are active on School Loop, Becker said.

“A lot of parents don’t have internet access at home,” she said. “Many don’t use technology at home or in the workplace, and some have a fear of it that gets passed on to their kids.”

Still, Becker and other educators across the district keep trying. They host parent workshops and offer time for moms and dads to use the computers at the schools as needed.

Lindbergh Assistant Principal Danyett Lee added that Lindbergh doesn’t have a parent-teacher-association, and the struggles with parent engagement go beyond cyberspace.

“Parents … don’t feel qualified to help at home,” she said. “Part of that is generational because the work these kids are doing is more advanced than ever before.”

No two schools are exactly alike

The issues Lindbergh faces aren’t universal. Each school in the district has to uniquely navigate 21st century technology in a way that is a best fit for its own student population.

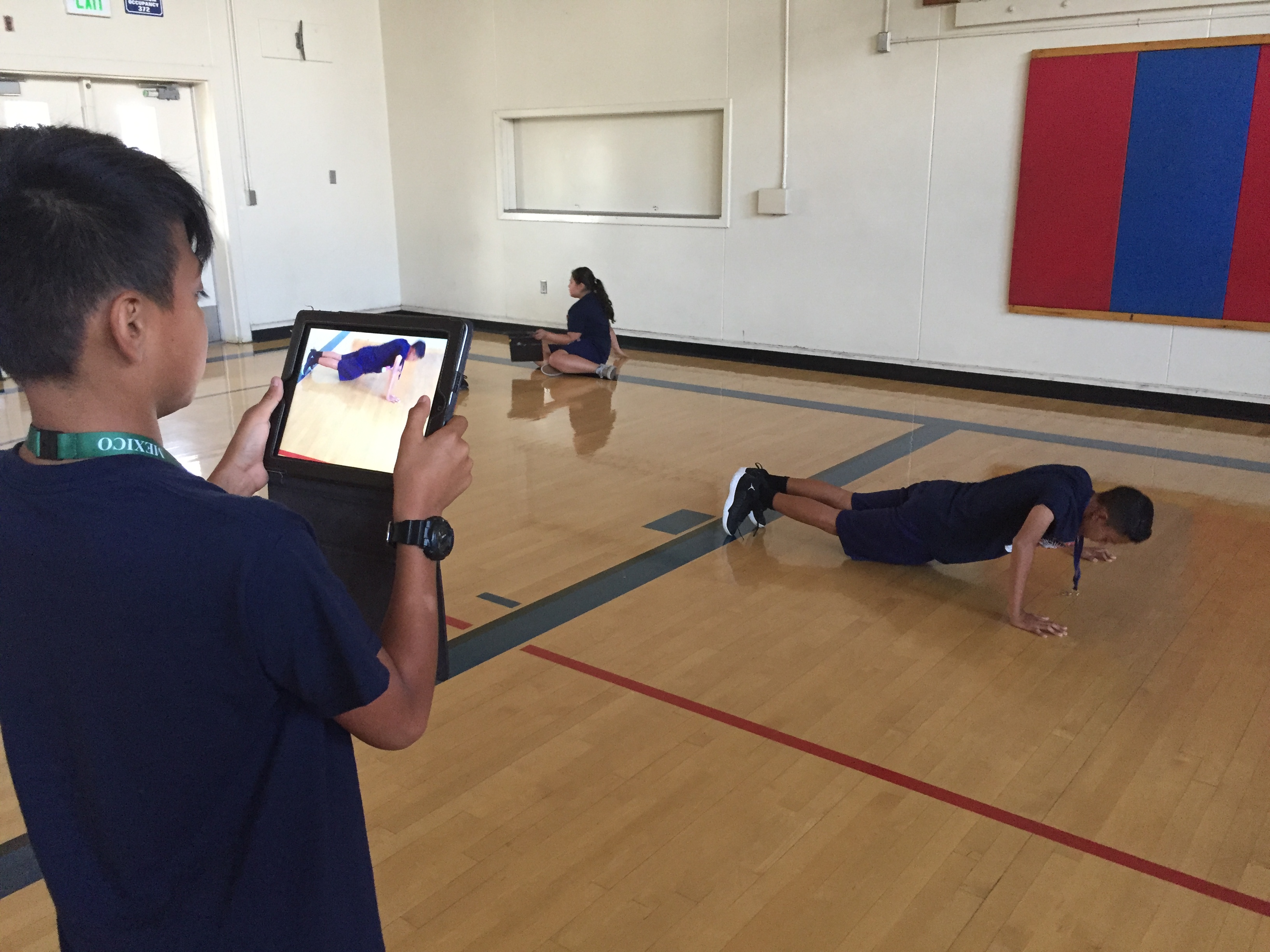

Technology has been integrated into every class possible at Lindbergh Middle School, including physical education. As an example, Matthew Torres uses one of the school’s iPads to film fellow student Ivan Vaca perform pushups. The boys will use the footage to critique and correct their technique. Gazette photo by Ashleigh Ruhl

In general though, Chandrasekhar said the district is gravitating toward Chromebooks. The cost of a Chromebook, she said, is about $250, compared to iPads that range from $600 to $800.

Various federal, state and private grants help offset the cost, which has been especially substantial in recent years because state testing shifted from paper to computers. Some private entities also provide support, including some active PTAs.

Typically, the iPads are available for students to check out and take home, but that varies by school. Chromebooks usually are not available for home use, but some sites, especially those with English as a Second Language (ESL) students, allow some limited checkouts.

All elementary schools in the district are using ST “Jiji” Math, a tablet application that teaches elementary school–aged students to think critically and solve math problems with some guidance from a virtual penguin named Jiji, Steinhauser said.

Many students opt to use the program outside of the classroom, but residential access isn’t a requirement, and he said students don’t need tablets at home to keep up with their peers.

“If you go to school, you don’t need to do it at home,” he said. “You could finish faster at home, and there are kids who do that, but no one is at a disadvantage… Anyone who finishes at a certain level will do well on state exams.”

‘It’s amazing what we are able to do’

One of LBUSD’s newest facilities is McBride High — the state-of-the-art eastside school opened in 2013 and is open to 700 students from throughout the district. About 43% of the diverse student population at the small thematic school comes from low-income families, which is below the district average.

Principal Steve Rockenbach said students there are assigned to career pathways such as health and medical; public services and forensics; and engineering. McBride’s 32 teachers keep those tracks in mind when integrating technology into their classrooms, always trying to relate lessons back to real-life examples.

They’ve used video conferencing so that students can virtually “meet” experts in related careers; the school boasts a high-tech microscope in its forensics lab; and health students are looking forward to the addition of a patient care simulator; among other ongoing upgrades.

“It’s amazing what we are able to do,” Rockenbach said. “The tools these students have are far greater than we’ve ever had.”

McBride has 440 Chromebooks and every student has an iPad available to use, which they can take home. The school also has three labs loaded with gadgets for advanced students taking classes that require engineering software or other specialized programs.

Brian Everson, who has taught English and history courses for a decade, said technology has transformed his job for the better.

“I’m not a tech-savvy person — I don’t have a TV, and we’ve gone pretty much screenless at home — but I’m a convert when it comes to using technology in the classroom,” he said.

Whether they have access at home or not, it’s common to see McBride students — and pupils at high schools throughout the district — working on the public computers during their unscheduled periods, lunch breaks, early morning and after-school hours. Some schools are open on Saturdays too.

Among those usually studying on her off-hour is 17-year-old Allison Duch, who is considering a career in criminal justice. She recently used a school Chromebook to complete her forensics homework, tapping into the campus wi-fi, which is piped in at the same 1G speed across all schools in the district.

“I don’t need the internet at home to do most of my homework,” she said, even though she has residential access.

The same goes for student Lili Nonskul, 17, who is plugged in at home but prefers to get her work done on campus. Nonskul was recently applying for colleges during her unscheduled period at school.

“Why not try to get things done during my free time here at school?” she said.

Steinhauser said it’s been important for the district to provide youngsters with communal spaces where they can plug in to complete their work when necessary. He noted that the city has done a good job of adding wi-fi to other public spaces, such as libraries and parks, and said he hopes the whole city will eventually be wired so students can take their school-provided laptops anywhere.

“The long-term goal for everybody is how do you make sure the entire city and the area the district covers has wi-fi access so kids can have that,” Steinhauser said.

Controlling public wi-fi may be beyond the purview of LBUSD, but Steinhauser said what the district can do is keep closing the digital gap with devices and in-class programming.

“When you can look at a school like Lincoln and a school like Newcomb, and both have a 1-to-1 ratio of students to devices, then there isn’t this great divide — that’s a great equalizer,” the superintendent said. “The challenging part is keeping up with it and helping everybody use it in the most efficient and effective way.”

Comments are closed.