City leaders are on the verge of unveiling a 300-page report on a project that holds the potential to connect everyone in Long Beach to the Internet in the coming years and nearly double the number of city-owned fiber connections.

It would make it easier for residents, especially in the North and Westside communities, to have more access to affordable, quality Internet.

Nearly 16% of Long Beach households lack an Internet subscription, which is defined as someone who either has broadband from an Internet service provider or a smartphone with a data plan, according to the 2016 Census Bureau American Community Survey, released in late August.

Related

Can Long Beach be the Next Burbank or Santa Monica?

Further insight into the Census data reveals that 74.7% of households have broadband from an Internet service provider, while 9.5% connect to the Internet only with a smartphone, leaving 15.8% of homes with no Internet access at all.

But whether easier access to affordable, quality Internet will happen depends on whether the city can afford to build the infrastructure needed to extend the network, as well as its ability to strike deals with the private sector to offer affordable coverage, especially in underserved areas.

In a recent Long Beach City Council study session, city officials said it could earmark about $12 million to put in a fiber network that could connect city facilities to high speed Internet. That’s part of a larger $88 million cost to upgrade the city’s outdated digital infrastructure.

The Fiber Master Plan, a long-awaited document nearly two years in the making, has been completed and is expected to be presented to the city council in the coming weeks.

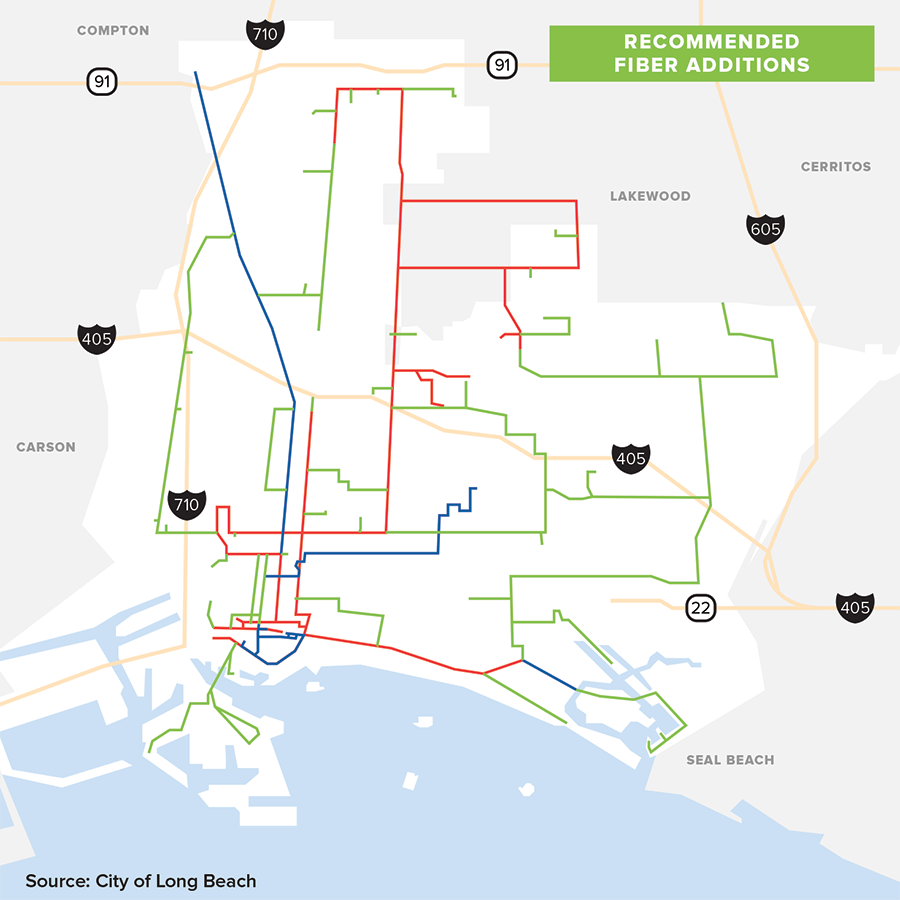

The initiative by the Technology and Innovation Department explores several ways to foster city-wide connectivity, from deployment scenarios and their costs to various implementation opportunities, such as the development of a small cell policy and the use of a “Dig Once” concept that would allow the city to save money by pairing the creation of fiber optic infrastructure with scheduled public works projects.

“This lays out ultimately what we have, where the gaps are and where we need to grow to really tie the city together,” John Keisler, director of economic and property development for the city, said. “This is a playbook for how we deal with core services, deal with existing needs and the cost to build that out.”

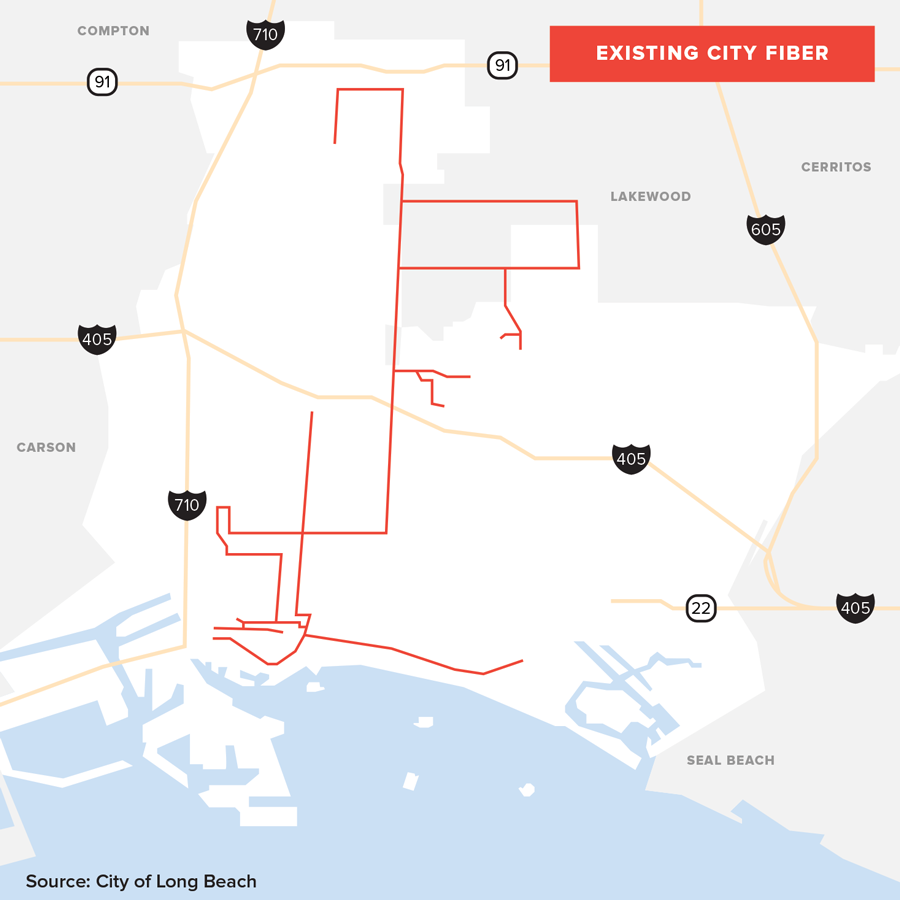

Long Beach has about 62 miles of city-owned fiber that links city facilities and manages traffic signals at high volume intersections. The plan is to expand the network to 110 miles.

A community that prides itself as a “Top 10 Digital City” by the Center for Digital Government, Long Beach is aware of its residents’ own lack of Internet access, especially in the city’s North, Central and Westside neighborhoods.

Long Beach 1st District City Councilmember Lena Gonzalez has seen firsthand her neighbors’ struggles to connect to fast, reliable Internet at home. There is no library in her district, and the closest one is the Main Library at the Civic Center, which is too far a distance for many of her constituents to travel. In response, in the last two years she has hosted youth camps to teach children in her district about coding, game design and how to use PowerPoint.

“It’s really great, but they don’t have the opportunity to do this at home,” said Gonzalez, who recently announced at her “State of the 1st District” address that bridging the digital divide would be one of her top priorities.

Vice Mayor Rex Richardson, whose 9th District includes the northernmost part of the city, said his community has Houghton Park, the city’s most utilized community center, and the Michelle Obama Neighborhood Library, one of the most modern and in-demand libraries in the city.

“The stories I have are of teachers who are pulling money out of their own pockets to provide resources in their classrooms,” he said. His focus is trying to integrate city infrastructure to connect the Atlantic Avenue corridor in his district to a city-owned fiber network.

Last year, Richardson started a project called UpLink, which involved installing fiber security cameras from the Michelle Obama Library to Jordan High School. “And that’s the first step,” he said. “There’s still more to do: low cost Internet is first; and we still need a robust laptop and mobile device checkout program.”

Richardson said there needs to be more infrastructure and integration, and access to devices and low-cost connectivity. “Look, there is enough infrastructure here to be really forward-thinking in closing the digital divide,” he said. “It takes focus and leadership from our school district, city, libraries and parks.”

Connectivity Issues

The impetus for the Fiber Master Plan came from the city’s Innovation Team in 2015.

“The team was looking at solutions to reduce disparity in terms of equity and economic outcome,” Keisler said. “What are the drivers of the new economy? Over and over again, connectivity kept coming up, [having] access opportunities of producing, consuming and transacting goods and services online.”

About 4,800 businesses in the city’s midtown area were studied, including those along Anaheim Street. Officials discovered that 40% of the businesses on Anaheim had no Internet connectivity or Internet presence. “That was a big finding in the original research,” Keisler said.

That fall, the city partnered with California State University, Long Beach, to track the progress of 12 entrepreneurs. Findings revealed that not having access to high quality, affordable Internet was a barrier to becoming more successful.

“The communities that are not connected [to the Internet] are not connected to the economy either,” Keisler said. “The information economy has fundamentally changed every segment of every industry in significant ways.”

Long Beach’s biggest industries – logistics, manufacturing, health care, and hospitality and leisure – are heavily technology-focused in terms of strategies and service delivery, he said.

“This is the new high-tech industry that fuels the economy,” Keisler said. “This is a utility as important as electricity and water.”

The city hired The Broadband Group in early 2016 to conduct a $25,000 study on what the financial model might look like if the city expanded its network and leveraged a municipal fiber network for private sector use.

The city has considered existing examples, such as Chattanooga, Tennessee, which spent about $330 million to build out a fiber network it owns, operates and maintains as a utility.

What about relying on the private sector to expand access in Long Beach? For many companies, that has been a tough sell, Keisler said. Some see putting fiber in the ground as an expensive and time-consuming process involving plan submittals and blessings from public agencies.

#AskLBMC: What is dark fiber?

Posted by Long Beach Media Collaborative on Wednesday, November 8, 2017

The expansion of Google Fiber, the tech company’s attempt to provide Internet service with gigabit per second speeds for downloading and uploading, has slowed to a crawl five years after it launched in Kansas City.

“For a city, it’s a core competency of ours to be working in the ground, working on sewers [and] water systems, [and] repaving streets,” Keisler said. “And we can coordinate that work. When Gas and Oil rips up a street to fix a pipe, we can lay conduit and pull fiber when ready. The private sector doesn’t have that core competency.”

City officials also have explored the concept of public-private partnerships. Santa Monica and Burbank, for example, have both found ways to connect fiber to One Wilshire, the data center that connects the West Coast, and leverage unused fiber strands to negotiate low Internet rates. Doing so allowed these cities to provide connections to residents in places such as a public housing project and a school district.

#AskLBMC: How do data centers like One Wilshire work?

Posted by Long Beach Media Collaborative on Wednesday, November 8, 2017

“That’s an example of what a city can do,” Keisler said. “You can do cool public policy stuff if you own the hardware and can negotiate low rates.”

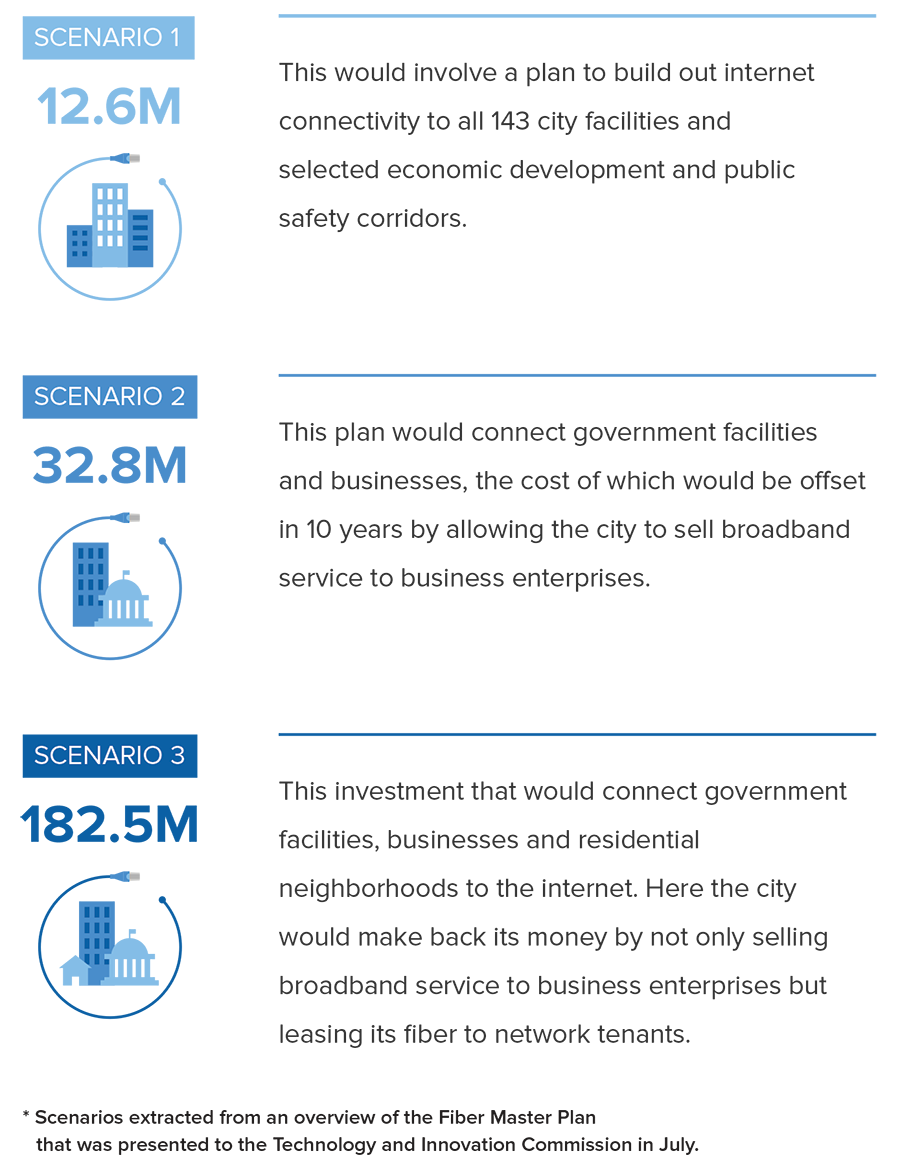

While the master plan has not yet been released, an overview of the plan was presented to the Technology and Innovation Commission in late July detailing three potential city build scenarios and their preliminary cost estimates:

- Scenario 1: This would involve a $12.6 million plan to build out Internet connectivity to all 143 city facilities and selected economic development and public safety corridors;

- Scenario 2: This $32.8 million plan would connect government facilities and businesses, the cost of which would be offset in 10 years by allowing the city to sell broadband service to business enterprises; and

- Scenario 3: A $182.5 million investment that would connect government facilities, businesses and residential neighborhoods to the Internet. Here the city would make back its money by not only selling broadband service to business enterprises but leasing its fiber to network tenants.

While the considerations and cost estimates presented to members over the summer were broad and prospective, it did emphasize the city’s direction to bridge the digital divide, something that the Long Beach Technology and Innovation Commission will be tackling in the coming months through a series of community outreach workshops and events, according to commission chair Robb Korinke.

“Long Beach, no different from many cities, has been subject to uneven coverage,” Korinke said. “It would be my ideal to eliminate that going forward. From the standpoint of education and job creation, having even access to high speed Internet is vital. People without it would be similar to towns bypassed by the railroad 200 years ago. It’s absolutely vital to moving a community forward.”

Expansion Efforts

Meanwhile, Long Beach is already finding ways to expand its network.

The city council recently authorized a deal with Crown Castle, an Irvine-based provider of wireless infrastructure, for a small cell solutions network consisting of 21 “nodes” that will attach to city street poles and other infrastructure around Shoreline Drive as part of a pilot program that will take place in the next few months.

The deal allows Crown Castle to lease public city space and make its nodes available to any cellular provider to share in its “fiber-fed network.” In exchange, Crown Castle gives the city some fiber strands to help build out its network. The city gets to collect $1,500 a year for every node through the Crown Castle deal.

The small cell solutions network of 21 nodes will be installed before the start of city’s biggest annual event, the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach.

“We’ll be able to leverage the new Crown Castle network in partnership with the city, reinvest in fiber or Internet access and ultimately expand the network to get into other neighborhoods,” Keisler said.

State legislation threatened to hinder the city’s progress. Internet service providers had been challenging the State of California to reduce local government control in order to quickly densify the cell network with more cell towers to increase bandwidth. But in October, Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed the bill.

“We want everybody in the city to have at least high-quality 4G cellular connection, [and] if not, a landline connection to broadband,” Keisler said. “We love the idea of expanding that, but it’s also something we want to be able to negotiate because so far they [companies] have not been willing . . . to go into a lot of the neighborhoods and provide the kind of Internet services needed.”

The Long Beach Public Works Department is working with the city attorney’s office to finalize changes to the municipal code that would give administrative approval to city engineers if an application for small cell antennas meets specifications, rather than going to the Long Beach Planning Commission. The changes are expected to go before the city council in the next two to three months.

“Crown Castle is the bridge to figure out what the specifications should be,” Keisler said.

Once city officials learn from that pilot, the city will draft a new ordinance that will standardize how and where small cell antennas should be placed in Long Beach, he said.

Meanwhile, Long Beach is hoping to pave its own path to One Wilshire.

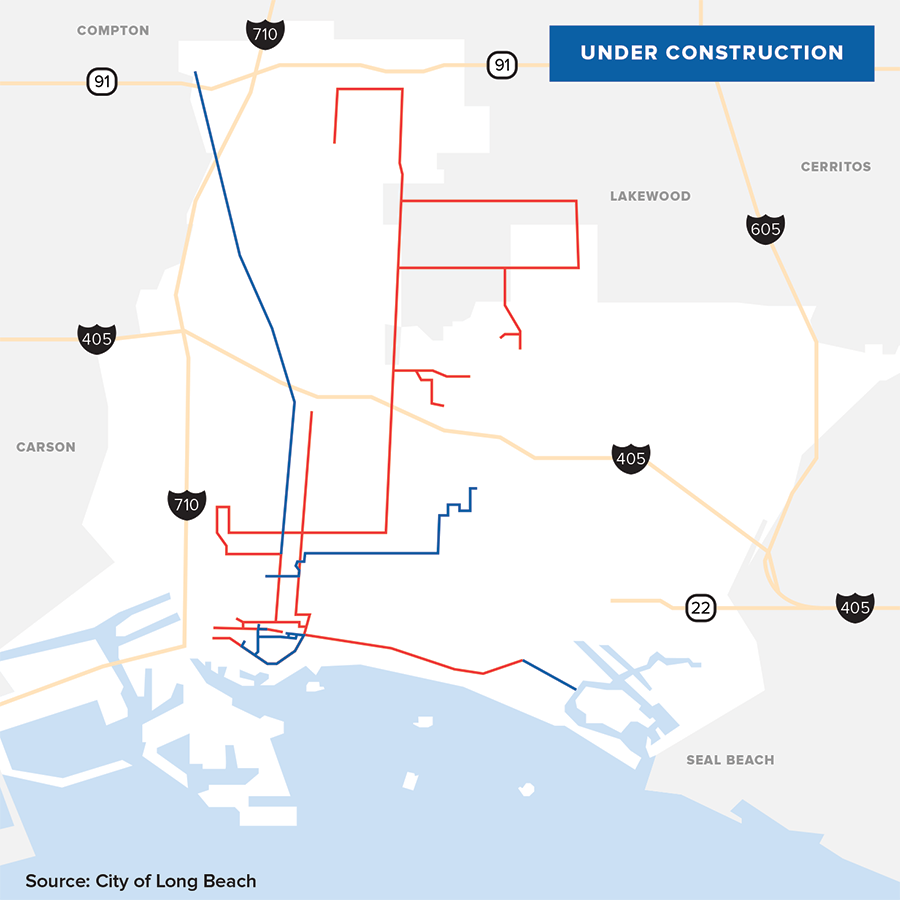

Thanks to a $993,000 Metro grant, construction will begin in early January on a nearly $1.6 million project to improve signalized intersections along 4.3 miles of the Metro Blue Line corridor, including 33 intersections from Downtown Long Beach to Wardlow Station and 52 intersections along Atlantic Avenue.

Set for completion in the late spring, the project, which will involve installing 14 miles of fiber optic cable and security cameras at strategic locations, will not only help trains communicate to signal controllers along the corridors when they’re arriving farther in advance, but also set the groundwork for better Internet connectivity down the road.

“We’re looking at this as the first leg to get to One Wilshire,” Keisler said, adding that Santa Monica’s first run of fiber was also a grant from Metro, which wanted to synchronize signals for buses.

The city’s fiscal year 2018 budget includes $400,000 for fiber to be installed when the city does street work, with a larger discussion about fiber plan funding anticipated in a city council study session as early as this month.

Gonzalez said she has already reached out to see how the city can logistically provide more connectivity. She also is looking to partner with an organization to provide low-cost personal computers and wi-fi while the city figures out the Fiber Master Plan.

Gonzalez said she looks forward to delving into the plan when it’s formally presented to the council in the coming weeks.

“We’ve got to get it right,” she said. “It’s got to be inclusive of everyone.”

Reporters Ashleigh Ruhl, Grunion Gazette, and David Downey, Press-Telegram, contributed to this report.

[Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story stated that the city gets to collect $1,500 a month for every node through the Crown Castle deal; the correct figure is $1,500 a year.]

Comments are closed.