When the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee decided to build out a fiber network, its aim wasn’t to become the fastest internet service provider in the United States.

In the late 2000s the city was just trying to install a state-of-the-art smart grid to limit power outages through its city-owned power utility, the Electric Power Board of Chattanooga (EPB). Becoming the first city in the country to offer extremely high-speed internet to all of its residents was an afterthought.

Now known as “Gig City”—because of its one-gigabit-per-second internet connection—Chattanooga often is cited as the gold standard of municipal fiber networks. Each one of its 170,000-plus residents has access to internet speeds that are over a hundred times faster than what most households in Long Beach can get, and at the same relative price point.

Internet in Chattanooga will run you $69.99 monthly, about the same as you’d pay in Long Beach for 100-megabit-per-second (Mbps) service; that’s one-tenth as fast. In Chattanooga, families with students qualifying for free lunch can get 100Mbps service for $26.99.

To put this into perspective, with a gig you could download an entire HD movie in mere seconds; with 10 gigs you and more than a thousand of your closest friends could host a really big Game of Thrones party, with each person streaming on their own device.

Installing the fiber was expensive for Chattanooga. In 2009, the city took out a $169 million bond and received a $111.6 million federal stimulus grant that helped cover the total cost to build out the $369-million fiber network that supports the smart grid and internet, television and phone services that run through the EPB.

But fiber now serves a dual purpose in helping the city to avoid power outages and provide high-speed internet to every part of the city.

The city laid down more than 9,000 miles of fiber in two years, using both underground installations and running the fiber cables above ground on telephone poles, and began to immediately sign up customers along the way rather than waiting for the completion of the entire grid.

EPB initially estimated that it needed 35,000 residential customers to be able to sustain the debt service on the fiber bond; as of November it had passed 94,000 residential users. It has now surpassed Comcast for the largest share of the broadband market.

EPB’s vice president of marketing J. Ed. Marston said that with the additional money generated from broadband subscriptions, the city has already paid back an additional loan to build out just the internet portion of its fiber network and is ahead of schedule to pay back the bond. The extra money the utility brings in goes to charitable causes within the region, re-investment in the city’s electric grid and other benefits that non-internet subscribers enjoy.

“We’ve actually used the revenues from the fiber optic business to prevent about a 7.5-percent rate increase on the electric side,” Marston said. “Our electric customers who don’t subscribe to the fiber optic services, they still get a real benefit because their electric rates are lower than they would have been if we wouldn’t have done this.”

But becoming Gig City did not come without a fight. As it turned out, internet providers weren’t keen on the idea.

Like many of the dozens of municipal fiber providers that now exist in the United States, Chattanooga faced legal challenges and attack ads as it announced its intentions to build out a fiber internet network to areas that the city’s incumbents—Charter and AT&T—would not service due to alleged cost barriers.

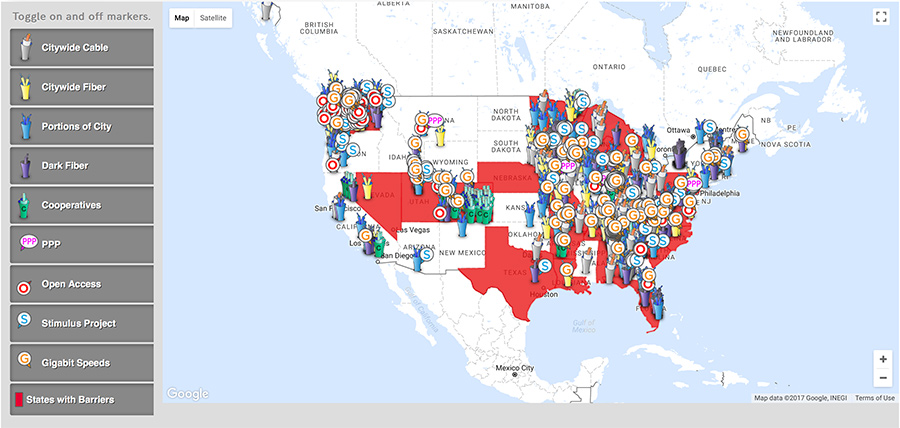

This interactive map from Community Networks “tracks a variety of ways in which local governments have invested in wired telecommunications networks as well as state laws that discourage such approaches.”

There were areas of town that were underserved, or unserved, by the two incumbents in the city which forced some residents in the more rural parts of town to seek out dial-up or satellite links to the web. Marston recalls the battle that ensued when the city announced its intentions to build out its own network.

“There was a massive advertising campaign that Comcast put out basically complaining about this coming service and asking people to call their city council people and city hall to let them know that they didn’t want the service,” Marston said. “They did a strong media blitz that lasted for several months and they only got about six calls and they were all saying ‘we want the EPB service.’ So it kind of backfired on them.”

He added that when EPB went online and the gigabit service became available in 2010 it also spurred competition among Comcast and AT&T. Once thought of as a lower-level priority for the companies, the city was bumped up in regard to infrastructure investments. In 2015, Comcast announced its rollout of 2-gigabit service to residences in Chattanooga—almost unheard of for residents

The gigabit internet has not only improved residential speeds dramatically in Chattanooga but has also served as an economic driver for the city. In addition to the projected $50 million in savings to its electric customer from its smart grid by preventing power outages, the availability of high-speed internet has helped draw new business to a town that, like many other industrial towns in the country, was struggling to find an identity.

Chattanooga now attracts companies like DC Blox, a data center developer, and Branch Technology, an Alabama-based architectural 3D printing company. A 2015 study released by the University of Tennessee Chattanooga found that the smart grid and the gigabit network had resulted in the creation of between 2,800 and 5,200 jobs in its first five years of existence.

That translates to about $865.3 million and $1.3 billion in economic and social benefits according to the study.

The Chattanooga story, especially the efforts of lobbyists and incumbents trying to prevent municipalities from taking their broadband fates into their own hands, is something Craig Settles is familiar with. Settles works as a consultant for cities looking to improve their connectivity speeds and helps them navigate the various roadblocks—legal and political—that await a city eyeing a faster municipal internet.

Settles, who primarily works with rural providers, as they’re often left on the back burner when it comes to internet service providers’ improvement plans, said that the same kind of issues can be found in large cities. He says the quality of infrastructure is often determined by the return on investment from a given area.

“If you’re in a low-income area, a place that’s not profitable for the incumbents, you’re not going to get quality customer service, you’re not going to get quality technology service or upgrades and that’s kind of where the starting point is,” Settles said.

For cities like Long Beach, where the existing fiber network does not reach every neighborhood and is considerably slower than Chattanooga’s, a build-out could make sense. City staff is set to present its options for a fiber master plan to the city council for a vote, possibly as early as December.

RELATED

Can Long Beach’s Fiber Master Plan Bridge The Digital Divide?

That plan includes tiered pricing of the options before the city. They range from a $12.6 million build-out that would interconnect city services like libraries, parks and other city facilities, to the most expensive option that has been cast as a Chattanooga-type build out. That option is projected to cost $182.5 million, of which the city could make money back by leasing it to network tenants and charging businesses for access.

There are, however, legal hurdles to building out a fiber network. In 2008, California legislators passed Senate Bill 1191, which laid out parameters for what services a city can and cannot provide. Included in that bill was a section on broadband services which states that communities can build out their own broadband networks but if an ISP “is ready, willing, and able to acquire, construct, improve, maintain, and operate broadband facilities” the owner of the network must sell or lease the network to the provider.

Laws like these are on the books in a number of states across the country, but Settles said SB 1191 is unique in the sense that California Democrats enjoy a supermajority in their state legislature and most of the other states on the list—Vice published a list of 21 states that have laws obstructing municipal broadband buildouts—are dominated by conservative lawmakers.

However, San Francisco seems willing to test those waters as its lawmakers pledged in October to connect all its homes and businesses to a fiber optic network that the city would build and maintain.

If Long Beach were to follow in San Francisco’s footsteps—the city has been public on its current stance that it is not interested in making internet service a city-run operation—Settles said they also need to also prepare for a Chattanooga-type blitz of negative public relations campaigns, predatory marketing where incumbents could suddenly drop prices to undermine the fiber roll out, and even political donations against elected officials.

Long Beach has five city council seats up for election in 2018.

“Any kind of larger, urban area you have to have the political will to go to bat,” Settles said. “Because there will be push back of one sort or another.”

What the City of Long Beach intends to do with its fiber master plan remains to be seen. The city has yet to vote on its fiber master plan options but seems intent on not becoming an outright utility. But that doesn’t mean a faster fiber network isn’t in the cards.

Bryan Sastokas, the city’s technology and innovation chief, said that even if the city opts to adopt the lower, less expensive option outlined in its fiber master plan, it doesn’t rule out expanding on it in the future. The city’s foremost concern is providing city services, Sastokas said, but it’s open to working in tandem to improve internet access.

“Our intent isn’t to compete in the marketplace, but to provide it to allow someone else to come in and build off of it and provide a more affordable service,” Sastokas said.

Whether that would be Frontier, Charter or another third party provider would have to be negotiated, but Sastokas said that even at the lower-tiered option the city’s fiber would be within about two miles of any point in the city. From there, if a third party wanted to lease access to the fiber skeleton it would be responsible for the “last mile” digs to individual homes.

With or without an internet service provider (ISP) tenant, Sastokas said the city’s fiber network needs to expand for a multitude of reasons, including upping the city’s ability to draw businesses to Long Beach as well as creating more equitable access to internet.

If the ISPs don’t capitalize on it the fiber “seeds” planted by the city in the coming years could make it more nimble to evolving methods of broadband delivery. Sastokas pointed to the recent 5G effort being made by the mobile phone industry as an example of how internet delivery to customers may change in the future.

However, those 5G mobile internet repeaters, or whatever else evolves in the industry will likely need fiber or some other wired connection to branch out from if they intend to deliver faster download speeds.

“We have to make this investment in order to have this set not only for today, but like the land use element, for ten, twenty, thirty years in the future,” Sastokas said. “We’re trying to look forward.”

Comments are closed.